Eye care professionals don’t always look like the patients they serve.

About 7.7 percent of ophthalmology residents are underrepresented minorities — compared with 30.7 percent of the U.S. population — according to a recent study in JAMA Ophthalmology.

Among practicing ophthalmologists: just 6 percent.

Representation is “much lower than it should be,” says Shahzad Mian, M.D., director of the ophthalmology residency program at the University of Michigan Medical School.

Meanwhile, the number of people with visual impairment or blindness in the United States is expected to double by 2050, according to National Institutes of Health data. Black Americans have the second-highest rate of visual impairment; Hispanics are expected to eclipse them by 2040.

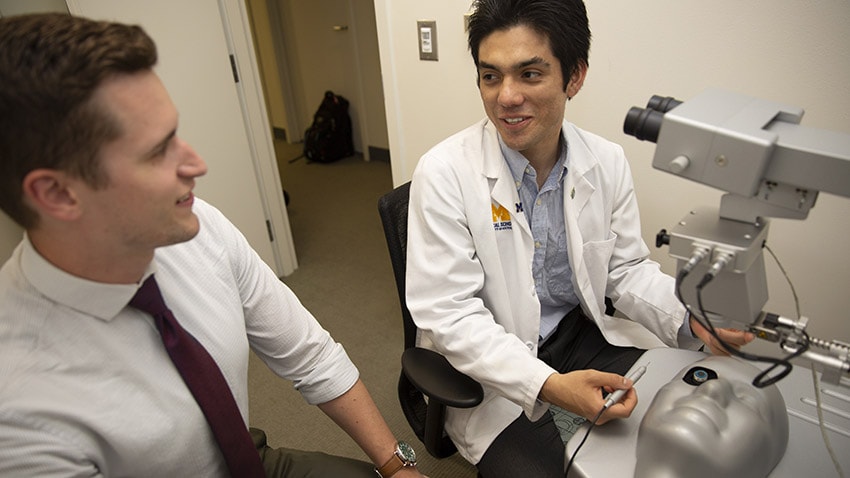

It’s why Mian and a recent U-M alumnus are working to diversify the field through a new effort that pairs medical students with first-year ophthalmology residents.

Known as the Mentorship-Led Pipeline Program, the partnership is designed to get more minorities at U-M interested in eye care careers. The effort, which launched in 2017, targets students just starting their M1 year — a busy time when coursework and career possibilities can feel overwhelming.

“It breaks down the intimidation factor a little bit,” says Kevin Heinze, M.D., a 2018 graduate of U-M’s medical school who recently began his postgraduate internship at St. Mary Mercy Livonia Hospital.

“The best way we can do this is to expose them early and provide enlightening activities to come learn about the field.”

Those activities include virtual reality surgical simulations and hands-on eye exam skills workshops. Three times a semester, resident mentors provide shadowing in a clinic or operating room setting.

The effort was inspired by Doctors of Tomorrow, a program that has paired first-year medical student mentors with freshmen at Cass Technical High School in Detroit since 2012. A recent study found that the yearlong partnerships benefit mentors and young participants alike.

Heinze, a former Doctors of Tomorrow mentor and mentorship director, knows the power that peer influence can have.

Mian does, too. He hopes the budding pipeline program can grow and impact more students who might otherwise find themselves drawn to other branches of medicine.

The ultimate goal: “enhancing their knowledge and skills within ophthalmology, providing mentorship and hopefully, in the long run, recruitment,” Mian says.

Early exposure to eye care careers

At U-M’s medical school, 19 percent of students in the 2017 entering class are from backgrounds underrepresented in medicine.

But 14 percent of U-M’s first-year ophthalmology residents are an underrepresented minority, Mian notes. That group is commonly defined as people of black, Latino and Native American heritage, though other ethnic groups fall under that definition.

Mian has several ideas about why the disparity is high in this track.

First, many medical schools don’t include ophthalmology as a required rotation. That means “many students don’t get exposed to the field early, or even late,” he says.

Second, the path to becoming a general ophthalmologist, which includes a yearlong internship after medical school followed by three years of surgical residency, can seem daunting.

“Because it’s a surgical specialty, people might think it’s too competitive or that they might not match,” Mian says. “Sometimes, it’s hard to know you’re capable of handling the workload. Having good mentorship can help you recognize that you can do this.”

Those are barriers that the new partnership is working to reduce not only through clinical exposure but also through casual dinners and professional networking.

Progress, likewise, might also come from informal conversation with older peers.

Early feedback of the program shows promise. In a survey of the pipeline’s nine participating M1s, all but one said the experience gave them strong interest in ophthalmology. The mentors (all seven of U-M’s first-year ophthalmology residents) rated the experience a 4.8 out of 5 on average.

Diverse doctors benefit communities

Heinze and Mian know that the pipeline effort is one step in addressing a bigger issue.

“There’s a huge disparity in vision care in the U.S. and worldwide based on racial and ethnic barriers,” Heinze says. “If we can diversify our body of providers, we can reach underserved communities easier.”

Doctors of color, he maintains, can have distinct impact among people of color — populations that might be reluctant to seek or receive treatment.

That scope can include primary and preventive care. Unlike doctors in some specialties, eye care professionals have the opportunity to build long-term relationships with their patients.

And the job’s everyday tasks — screening young children for glasses, for example, or helping older patients with glaucoma or macular degeneration maintain their sight — play major roles in maintaining quality of life.

Recruiting more doctors to provide these services in underserved areas is vital.

“We have to create those opportunities to get training,” Mian says. “Ophthalmologists serve a major role in helping these communities.”