When it opened in 1906 on Catherine Street near the University of Michigan’s main hospitals, the stately brick State Psychopathic Hospital meant something new in the world of mental health.

Funded by the state, and staffed by university faculty and staff, it was a psychiatric teaching hospital – a place where people with serious mental health conditions could get a definitive diagnosis and start treatment, while U-M medical students learned about, and faculty physicians studied, their conditions.

The 41-bed SPH admitted patients who could pay for their own mental health treatment, as well as those ordered into care by the justice system. Rather than a long-term warehouse, as so many asylums of the day were, it represented a new era in mental health care, research and training. It even had a laboratory where brain samples from patients across the state could be probed, to look for clues about what caused mental illness and neurological disease.

Fast forward to 2020, and Michigan Medicine’s mental health care teams, researchers and educators are still focused on that goal. As part of the 150th anniversary of U-M’s academic medical center, here are some highlights from that history:

The originators

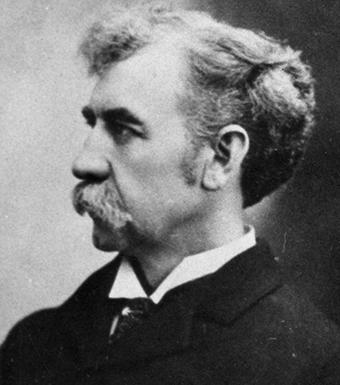

The roots of mental health training and care at U-M actually date back to 1890, when William James Herdman, M.D., became the first Professor of Diseases of the Mind and Nervous System, and of Electrotherapeutics.

He formed ties between U-M and the state’s asylums, including opportunities for medical students to travel to some of them to learn about mental illness and its care. Meanwhile, the Homeopathic Medical School that U-M ran at the time hired its first faculty focused on mental illness in the 1890s. (The school and its hospital closed in the 1920s.)

By the late 1890s, after working with the directors of asylums across the state to understand their needs, Herdman convinced the University’s Regents to approve the plan for partnering with the state on the new hospital.

In the allopathic, or main, Medical School, the two disciplines we now call Neurology and Psychiatry were intertwined for decades. Asylums and the state hospital at U-M treated people with what we now think of as mental illness, such as schizophrenia, as well as those with neurological conditions such as epilepsy. But as understanding grew about the conditions they encompassed, the disciplines grew further apart, splitting in 1920.

Albert Barrett, M.D., who had come to Michigan to lead the SPH’s pathology programs, succeeded Herdman in 1907, and led the further development of programs and research until 1936.

He and others had innovative beliefs about the treatability of mental illness, and the importance of training specialized medical staff to care for patients as well as trying to keep patients in hospitals and asylums for short periods and allowing those with less-severe illness to receive care closer to home.

The next generation

By the 1930s, the SPH was crumbling, and the new department chair, Raymond Waggoner, M.D., led the effort to build a new facility attached to the rear of the main University Hospital that had opened in 1925. Opened in October 1939, it was called the Neuropsychiatric Institute.

Still state-funded, and university-run, the NPI more than doubled U-M’s inpatient psychiatric capacity to 85 beds. It had a dedicated area for adolescent patients as well as spaces for physiotherapy, hydrotherapy, exercise, occupational therapy and a lecture hall that doubled as a theater and a new neuropathological laboratory for studies of the brain.

After World War II, the state funded a Veterans Readjustment Center on the northern edge of the medical campus, where veterans could receive psychiatric observation and care from U-M teams while enjoying recreational facilities. A new outpatient psychiatric clinic opened in what we now call the Med Inn building.

Psychiatric care at U-M in the middle of the 20th century focused on psychoanalysis, a field rooted in the teachings of Sigmund Freud. Practitioners believed that unconscious conflicts caused mental illness, and that intensive long-term care in sessions talking with psychiatrists could help. U-M became a training ground for new practitioners of the American form of this approach, though more biologically based treatments also were used in combination and studied in research.

Mid-century modernization

As U-M began to develop plans to expand treatment capacity for children with all types of illnesses, mental health got the first dedicated building, in 1955. Waggoner used his political savvy and connections to promote state funding to support a new facility just for the treatment of children with emotional and psychological conditions.

The Children’s Psychiatric Hospital, which was meant to be joined later by a comprehensive children’s hospital that never materialized, stood where the Rogel Cancer Center and its parking structure stand today.

With 75 beds and facilities for schooling, recreation and treatment, it sought to help children with all aspects of life, and many stayed for months or years. Teachers and mental health specialists partnered for an innovative approach, and also conducted research on its effects.

Meanwhile, the effort to bring modern scientific tools to bear in understanding mental illness also launched in 1955, with the formation of the Mental Health Research Institute or MHRI. Its building, which still stands at the corner of Zina Pitcher Place and Catherine St., opened in 1960 as a home for research on the genetic, molecular, systemic and societal roots of depression, addiction and more.

U-M psychiatrists also helped lead the way on better classifying mental illnesses and tracking their incidence and course using statistical methods.

A changing focus

As the field of psychiatry shifted away from psychoanalysis, and toward more biologically based treatments such as new pharmaceuticals, and the state ended its support for U-M’s programs, care and education changed markedly beginning in the 1970s.

Inpatient units in the new University Hospital built in 1986, and the expansion wing of children’s and women’s facility in 1990, provided for more short-term hospital care for adults and young people in the aftermath of psychiatric crises. Partnerships with Washtenaw County to create a 24-hour psychiatric emergency service, and with the VA Ann Arbor hospital to provide inpatient care for veterans with mental health needs, arose.

Training of medical students, nursing students and social work students in mental health care grew. But now, it wasn’t just for those who would devote their careers to mental health, but also those who would become more general practitioners in a time when many people with mental health concerns receive their care from a primary care practitioner.

The 21st Century

In October 2006, another path-breaking mental health building opened, a few miles away from the one that had opened a century before.

The Rachel Upjohn Building on the East Medical Campus provided a home for the world’s first comprehensive Depression Center, which was founded in 2001 in an effort led by John Greden, M.D., who chaired Psychiatry from 1985 to 2007.

The new building also greatly enlarged U-M’s space for all types of outpatient psychiatric care and innovative research on everything from psychosis to addiction. Renovations to the adult inpatient unit, and a new pediatric inpatient unit in the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, improved the environment of care.

Researchers from across U-M’s three campuses who do data-driven research on mental health care and substance use disorders, and the policies that govern their delivery, make up a sizable portion of the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation that launched in 2011.

In 2019, the institute once known as MHRI (and for a time the Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience Institute) took on a new, university-wide scope, as the Michigan Neuroscience Institute. As mental health research at U-M enters its 131st year, MNI seeks to connect neuroscientists who perform research and train rising brain scientists in seven U-M schools and colleges and 15 institutes and centers.

Today, 130 years after U-M hired its first professor of mental health, people with mental illness who might once have lived out their lives in an asylum can instead live independently with help from modern therapy and trained specialists, informed and transformed by the research of decades past. Society’s stigma against people with mental health conditions has eased, but not vanished.

But the national shortage of mental health professionals, differences in insurance coverage and health policy for mental and physical health care, and the enduring mysteries of what causes mental illness and what can help those with them, persist.

Sources: University of Michigan Department of Psychiatry from 1955 to 2014, Laura Hirshbein, M.D., Ph.D.

U-M Encyclopedic Survey: 1942 and 1975