Whether they switched to working from home in an arrangement that was more flexible than before or tacked on even more hours as an essential employee, health care workers have had a lot to adjust to in 2020.

In a recently published survey of more than 800 people who work in the medical field, more than 85% of respondents said their mood was worse in March and April than before the pandemic hit. And though the changes to their sleeping patterns differed depending on the group, more than 70% of the participants’ sleep patterns changed in some way during those first months of stay-at-home orders.

The abrupt transition was important to study as the pandemic continues, says lead author Deirdre Conroy, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at Michigan Medicine and the clinical director of the Behavioral Sleep Medicine Clinic.

“So many sleep complaints are related to scheduling issues, such as waking up for work, and the morning commute was abruptly stopped for many of us,” she says. “And on the other hand, so many people were working more hours at the hospital than they typically did or doing overnight shifts. The life these people were living became quite different, and so their sleep became quite different.”

Following your body clock

“People who never before were able to work from home were suddenly able to do this,” says senior author Cathy Goldstein, M.D., a sleep neurologist at the Michigan Medicine Sleep Disorders Centers and an associate professor of neurology. “We wondered how that affected mood based on our own experiences and what our colleagues were going through. We also wondered if the ability to sleep later, would allow people to sleep better given what we know about circadian rhythms.”

The natural midpoint of sleep is around 4 a.m. for the average adult, she says, which means the ability to sleep later allows for us to sleep in line with our natural clock. This could reduce sleep loss and specifically, reduces the curtailment of REM sleep, which takes place at the end of the sleep period.

Indeed, total sleep time didn’t change for those working from home, but these health care workers did stay up and sleep in a little later. That could indicate a shift toward a sleep schedule that better fits their body’s circadian rhythm, even if it doesn’t lead to more overall hours asleep.

Working in health care during a pandemic

While mood worsened for the majority of all survey respondents, the health care workers who were still reporting to work every day also slept for fewer hours than they had before.

“Typically the relationship between sleep, mood disorders and stress are bidirectional,” Conroy says. “When we develop sleep problems, it can influence mood, anxiety and other concerns. The reverse is true as well: if you are depressed, one of the symptoms can be a sleep disorder.”

Conroy says there’s also an intimate connection among sleep, mood and substance disorders, and she saw that in the survey results.

Although most of the sample did not increase their alcohol intake, “those people who did report drinking more alcohol during the pandemic compared to before drank a lot more,” she says, . About half of respondents said they’re exercising less, too, and half said they’re eating more food every day.

In addition, most people said they were consuming more news, which in turn means more screen time.

“If this had happened years ago, we would’ve had to get our news from live radio and TV broadcasts, but now we can view the latest news any time, for as long as we want,” Goldstein says.

It can be nice to catch up when you have a free minute during the day, but she encourages her patients to avoid bringing mobile devices into the bedroom. That way, you can escape both the melatonin-suppressing light and the activation of negative emotions that will affect sleep.

Supporting the front line

Researchers say the survey shows how important it is for everyone to prioritize their sleep and mental health, and the need for employers to support their health care workers.

Conroy, for example, joined one of the stress response teams in the Michigan Medicine hospital during the spring to provide social and peer support.

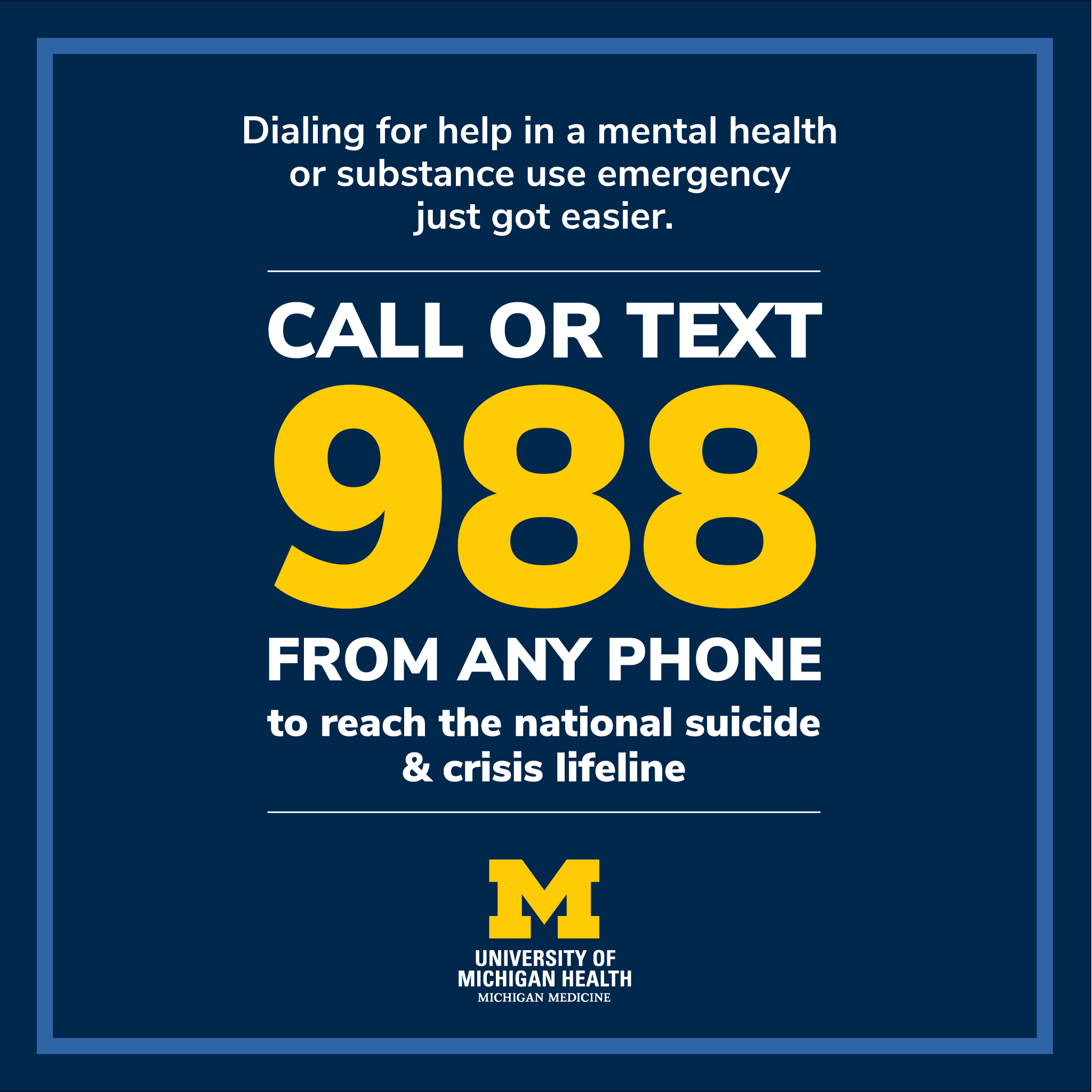

“Regardless of whether someone was at home or at work, mood worsened, and we need to pay attention to that and have resources available,” she says.

A variety of options would also be good, Conroy adds, given that some people may be interested in seeing a counselor virtually while others may dread the idea of one more Zoom call. Instead, those people could be open to playing a podcast or reading about tips they could use, or exploring another option to boost their mood.

And because those who continued to perform their health care duties in person reported sleeping less, employers should pay attention to sleep and emphasize its importance, perhaps providing as much scheduling flexibility or napping encouragement as feasible, Conroy says.

Paper cited: “The effects of COVID-19 stay-at-home order on sleep, health, and working patterns: a survey study of United States health care workers,” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. DOI: 10.5664/jcsm.8808

###