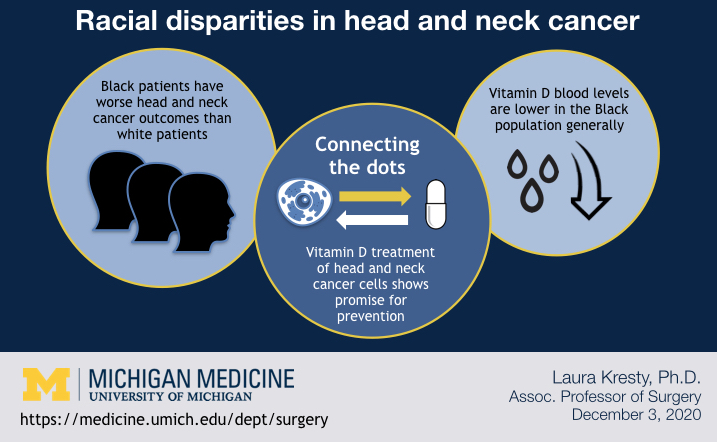

If Black patients experience higher mortality and recurrence of head and neck cancers than white patients, and Blacks generally have lower circulating levels of vitamin D than whites, what’s the relationship between those two factors?

Laura Kresty, Ph.D., M.S., Associate Professor of Surgery at Michigan Medicine, asked the question while still at the University of Miami School of Medicine, and continued to seek answers after coming to the University of Michigan.

The data in the study, published in the journal Nutrients, suggest that vitamin D may have a protective and therapeutic effect in head and neck cancers. Kresty was the primary investigator on the study.

A hole in the data

Kresty homed in on the question in Miami after a colleague there, W. Jarrard Goodwin, M.D., published on genetic mutations specific to the protein p53 in head and neck cancer patients. She noticed differences in the Black population and was intrigued, even though the sample size was small. She’d also seen a separation in the data for the p16 protein between Black and white patients in her own mutation analyses.

Both the p53 and p16 proteins play a role in tumor suppression.

It was known vitamin D was generally lower in Black people, and Kresty wondered whether it would be protective, but no one had done measurement of vitamin D levels in Black patients with head and neck cancer.

“It had been looked at in white people and we knew they had lower levels when they had head and neck cancer. We also knew Black people had generally lower vitamin D. It seemed like a hole in the data to focus on,” Kresty says.

Kresty and colleagues recruited 9 Black and 10 white patients newly diagnosed with head and neck cancer for the study. The participants completed surveys on dietary intake, risk factors, physical activity and sun exposure and had blood drawn for analysis.

The survey data was intriguing, but the layering of physical data painted a clearer picture.

“The truth is in the biologic measure,” Kresty says.

The metabolite 25-Hydroxyvitamin D was measured in patients, because it’s considered the most valid indicator of Vitamin D status.

The Black patients had lower mean circulating levels of vitamin D than the white patients —20 ng/mL vs 27.30 ng/mL. While that difference is striking, means can sometimes appear to narrow gaps. Black patients were overrepresented in the “very deficient” cohort, those with less than 20 ng/ml of vitamin D.

“The very low levels were in about half of the Black patients, where only 10 percent of the white patients had these very low levels,” Kresty says.

One trend the data found was a difference in sources of vitamin D between the groups; the Black patients reported getting slightly more from dietary sources than the white patients.

Some information about vitamin D intake in the survey pointed to behaviors that cost money, linking up potential socioeconomic factors, Kresty says. The Black patients were less likely to supplement vitamin D, and less likely to use sunscreen, instead shielding from the sun with hats and clothing.

Research paused, and revived

Kresty had planned to do molecular profiling of the patients’ tumors, but hit a speed bump when the majority of the Black patients opted not to pursue further treatment or surgery. What drove those patients’ decisions not to pursue more treatment wasn’t clear.

After Kresty came to the University of Michigan, the work was shelved for a while. Its revival was sparked by Alison M. Mondul, PhD, M.S.P.H., a co-author on the paper. Dr. Mondul had an interest in researching vitamin D in head and neck cancer patients and partnered with Dr. Kresty to conduct preclinical research.

The team at Michigan turned their attention to cell lines of head and neck cancer patients, treating the cells with vitamin D. The treatment significantly altered five mircroRNAs, which have a cascading effect on genes relevant to multiple cancer pathways and processes. Various genes were up-regulated and down-regulated in ways that show promise for vitamin D as a targeted cancer prevention treatment, according to the study data.

“It does touch on many regulatory processes involved in cancer progression and spread —metastasis—and cancer recurrence and response to therapy—resistance,” Kresty says.

A study looking into disparities reveals more disparities

Notably, the cell line work highlighted another disparity: The availability of head and neck cancer cell lines from Black versus white people. The study team was not able to locate cell lines from Black patients from the go-to sources of cell lines—American Tissue Culture Collection and its European equivalent— and thus conducted the in vitro work on cells from white patients only.

“There may be some in private collections that I don’t have access to or I don’t know about. It’s a void in the research community. It would be nice if people would isolate cell lines across more diverse ethnic and racial groups. That way we could conduct research in a manner that considers some of the biologic or the genetic diversity inherent across populations in context of our research,” Kresty says.

Having access to a more diverse patient population and tissue library may enable more targeted interventions, according to Kresty.

##

By Colleen Stone