Since its founding in 1850, the University of Michigan Medical School has forged a strong leadership role in American academic medicine.

Tradition of Excellence

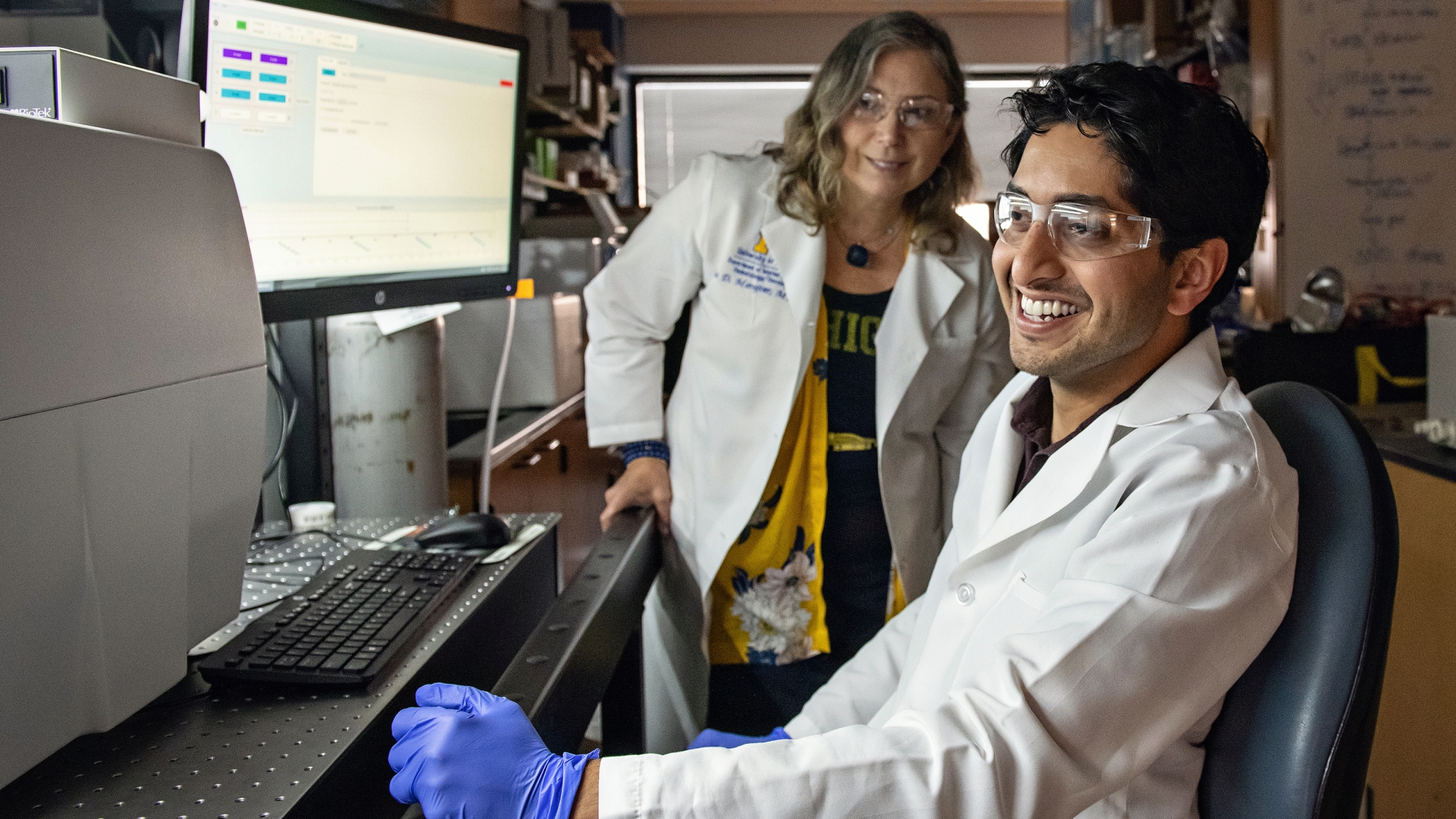

The U-M Medical School continues its long tradition of excellence with a diverse and outstanding student body, world-renowned basic science and clinical faculty, a completely revised curriculum for the MD degree, and exceptional facilities for patient care, education and research.

Our cooperative relationships with other U-M colleges and schools — including Public Health and Engineering — foster opportunities for learners to lead interprofessional teams and participate in creative research collaborations.

The U-M Medical School consistently ranks in the top of all medical schools in the country. It also ranks near the top among all medical schools in terms of National Institutes of Health research awards. And the Medical School is in good company. U-M’s College of Engineering, Law School, School of Business Administration, School of Dentistry, College of Pharmacy, School of Nursing, School of Public Health and School of Social Work all rank in the top 10 nationally.

The University of Michigan Medical School is fully accredited by the Liaison Committee of Medical Education.

UMMS was last reviewed by the LCME in 2020 and was awarded “full accreditation of the medical education program for an eight-year term.”

The next formal LCME site visit will take place in the 2027-28 academic year.

View research and education facts and figures at a glance, from numbers of learners in various programs to research and grant funding and awards.

Our impressive and far-reaching alumni base of more than 20,000 graduates includes leaders of Fortune 500 companies and faculty who occupy top posts at the best educational and research institutions around the world.

Early Firsts

The University of Michigan Medical School was the first medical school in the United States to own and operate its own hospital, among the first major medical schools to admit women, and the first major medical school to teach science-based medicine.

We also introduced the modern medical curriculum and the first clinical clerkships.

Education in Action

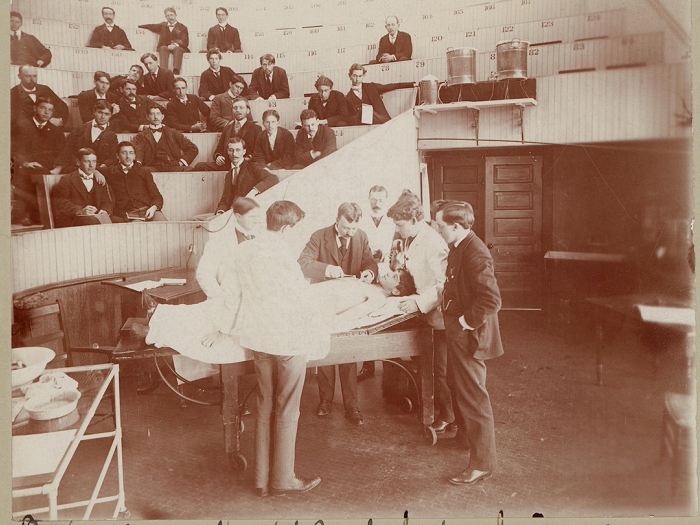

In the late nineteenth century, the U-M Medical School embarked on a mission to involve students as active participants in their education, rather than passive observers. It also taught students how to acquire and interpret information. Both teaching approaches were radical for the time.

In 1899, the U-M Medical School successfully introduced the concept of the clinical clerkship. Because U-M owned our own hospital, we could set up such clerkships directly at our hospital. Other medical schools had previously tried to incorporate such clerkships into their curriculum, but privately owned hospitals would not allow medical students to touch their patients.

Ever-Evolving Curricula

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the U-M Medical School led efforts to revise and improve medical curricula by doubling the length of the program for the MD degree and by integrating clinical rotations into every student's course of study. In the 1950s through the 1960s, we made sweeping changes to our medical curriculum. For example, we made sure that students had early clinical contact with patients, and we introduced an interdepartmental course in the neurosciences.

The late 1960s was an era of increased clinical training in the first two predominantly basic science years of medical school. The U-M, along with many medical schools across the country, adopted an interdepartmental Introduction to Clinical Medicine course that would remain a staple of the first two years. We also introduced senior year sub-internships, which are still part of the advanced clinical curriculum.

For 175 years, since our founding as the University of Michigan's medical school in 1848, we have been on a quest to transform the future of health care through leading-edge medical education, groundbreaking discoveries, and extraordinary care.

More than 20,000 alumni have graduated and thousands more have held residencies and fellowships here. The University of Michigan Medical School opened its doors in 1850 and became U-M’s first professional school.

In 2025, the University of Michigan Medical School will celebrate 175 years of educating some of the best and brightest minds in medicine.

The first class of medical students paid $5 a year for two years of education. In keeping with the times, none of the members in the first class was a college graduate. Instead, to gain admission, medical students had to know some Greek and enough Latin to read and write prescriptions. The curriculum consisted of lectures, and the second year was a repeat of the first.

The first woman graduate, Amanda Sanford, received her U-M Medical School degree in 1871. Two years later, W. Henry Fitzbutler — the son of a slave — became the first African American to graduate from U-M Medical School.