Many health conditions and diseases can be improved by simple behavioral changes, such as eating plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables, managing stress and getting enough sleep.

But what happens if patients don’t have the means to access healthy food or don’t know where they are sleeping that night because they are homeless?

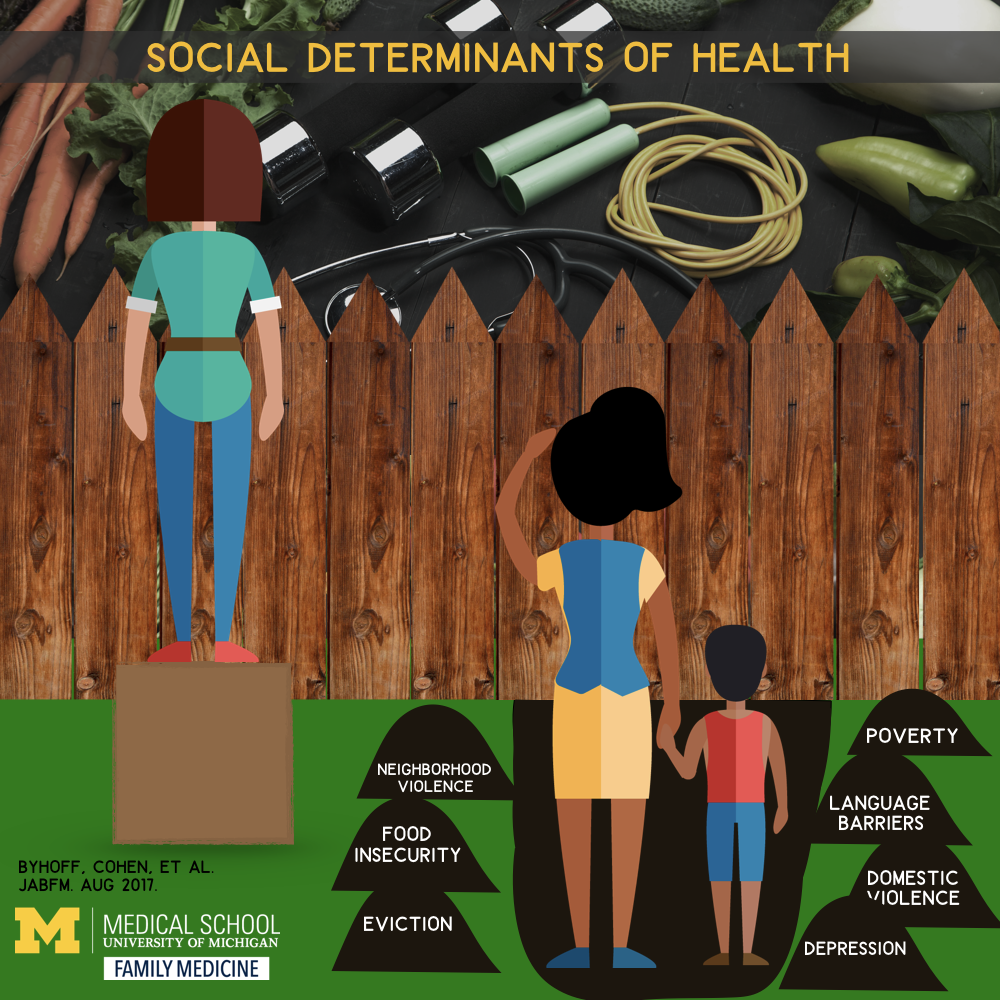

To better address unmet needs that can negatively affect a patient’s health and well-being, University of Michigan researchers recently analyzed how community health centers across the state screen for what are commonly termed social determinants of health.

This usually involves a deeper line of questioning than a typical primary care checkup.

“If we don’t know that people don’t have enough food to eat, or they can’t afford their medication, or their electricity keeps getting cut off so the insulin in their fridge goes bad, we can’t adequately provide care for them,” says Alicia Cohen, M.D., M.Sc., clinical lecturer in family medicine and an advanced health services research fellow at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

Which is why Cohen and co-lead on the project, Elena Byhoff, M.D., M.Sc., forged an academic-community partnership with the Michigan Primary Care Association, a statewide consortium of health centers, to understand screening practices for social determinants of health.

Those practices, they know, are vital to treating at-risk patient populations — and could have implications for how other health care sectors provide care.

“Screening for social determinants of health is an important first step in addressing the major causes of poor health and health care outcomes in vulnerable patients,” says Renuka Tipirneni, M.D., M.Sc., the study’s senior author. “As community health centers have a long history of looking outside the walls of the clinic to address these root causes, other health systems may learn a lot from their example.”

A complex issue

The researchers examined the practices of 23 health center organizations representing 167 delivery sites. They analyzed the types of domains screened for (such as financial hardship, social support and health care access), where and when the screens were administered, and by whom.

Although the group’s findings, published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, were promising, they also signaled that there is more work to be done.

Says Cohen: “We found that Michigan health centers are routinely screening for unmet social needs, and there was broad consensus regarding a core set of domains that largely aligned with emerging expert recommendations.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Academy of Medicine point out that the United States spends more money per capita on medical services than other nations but less on social services. Countries with higher ratios of social services spending compared with health care services spending have heathier residents who live longer, the organizations note.

To that end, they suggest that health systems screen patients for key social and behavioral determinants of health including employment status, education, physical environment, material hardship, mental health, trauma or violence, and veteran status.

“We recognize that unmet social needs have critical implications for health, and our ‘eyeball’ test is incredibly poor,” says Cohen. “You can’t tell by looking at a patient if they are struggling to put food on the table or pay rent.”

Making a connection

To better address the unmet social needs of patients, Cohen says doctors must first realize those struggles exist.

While there is a consensus about which domains health centers should screen for, the study highlighted the variation among how questions were asked and administered.

For example, Cohen and her colleagues learned that some health centers ask patients a single question to screen for financial hardship; others might ask several, more detailed questions specific to difficulties with housing, food, utilities, transportation and affording medication.

Differences were also found when evaluating who administered the screenings and how often they occurred.

Some health centers screened only new patients or during annual visits. Others screened patients more frequently or focused on specific at-risk populations. At some centers, patients filled out a questionnaire; others spoke directly with a medical assistant or clinician.

The variation isn’t necessarily problematic, Cohen says.

“It’s important to have some sort of standardization across measures, but there is also really a need to allow individual practices to tailor screenings to best fit their individual populations,” she says. “Future work is needed to come to consensus on a core set of evidence-based practices that also allow for tailoring to the needs of local communities.”

Next steps

The partnership between Michigan Medicine and the Michigan Primary Care Association will continue. During the next research phase, the study team will more closely examine how health centers implement screening by visiting in person and interviewing staff.

“We want to see in real time what this looks like,” Cohen says.

Face time with doctors, nurses and other staff members will help the researchers get a better sense of how screening is integrated into clinical workflow.

While screening is an important and necessary first step, many providers and practices are hesitant to implement systematized screening without a reliable referral process in place.

“It will be important to build on our findings with the MPCA to ensure that providers — both clinicians and support staff — feel that they have the ability to help patients once gaps are identified,” Byhoff says. “Screening is only half the battle.”

The other question the researchers hope to answer: What happens with the information when patients report unmet social needs? In the health centers studied, 99 percent of such detail is entered into a patient’s electronic health record — but how the data are used to guide treatment is not as well understood.

Some health centers may use a fairly streamlined approach, such as providing a patient who screens positive for food insecurity a list of area food banks or a referral to a community organization. Other health centers may provide longer-term follow-up with the assistance of a social worker or community health worker.

“Given the increasing emphasis on addressing community health needs by Medicare, Medicaid and other commercial payers, there is growing recognition of the urgent need to develop best practices for identifying and addressing social determinants of health in order to more meaningfully improve patients’ health,” says Cohen.

Read the original press release by Lauren Love on the MHealth Lab blog.

Article Citation: Byhoff E, Cohen AJ et al. Screening for Social Determinants of Health in Michigan Health Centers. J Am Board Fam Med, 2017 Jul-Aug; 30(4):418-427. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2017.04.170079

Discover new research on preventive medicine from the Department of Family Medicine.