DocsWithDisabilities Podcast #21

NAAHP Pre-Med Panel

Lisa Meeks:

Thank you so much for joining us today for this special edition of the Docs With Disabilities Podcast. We were brought together due to a cancellation of the National Association of Advisors for the Health Professions (NAAHP) conference. But we are committed to bringing you the information despite the pandemic and hope that this podcast reaches all planned attendees and more.

There's an intense competition for admission to US medical schools. Only 40% of the over 57,000 applicants to begin MD programs in the fall of 2018 matriculated. And only 38% of the over 8,000 applicants for DO programs, matriculated. All students face challenges in the admissions process, but pre-medical students with disabilities, whether they're learning, psychological, physical, sensory, or chronic health, face additional challenges, which can be grouped into three categories.

First, students with disabilities need to determine whether or not they're going to disclose information about their disability. And if so, when and at what stage of the application process will they disclose. Second, students with disabilities need to identify schools that will offer the best environment and resources for them so that they can thrive as an individual and a person with a disability. Oftentimes this involves considering the school's technical standards and its climate. Third, requesting accommodations can be scary, but it may be needed for various stages of the admissions process, including evaluations associated with admissions review like the Casper or the MMI or logistics for the interview day. Today we will address these items and we're excited to bring you this podcast alternative to the conference.

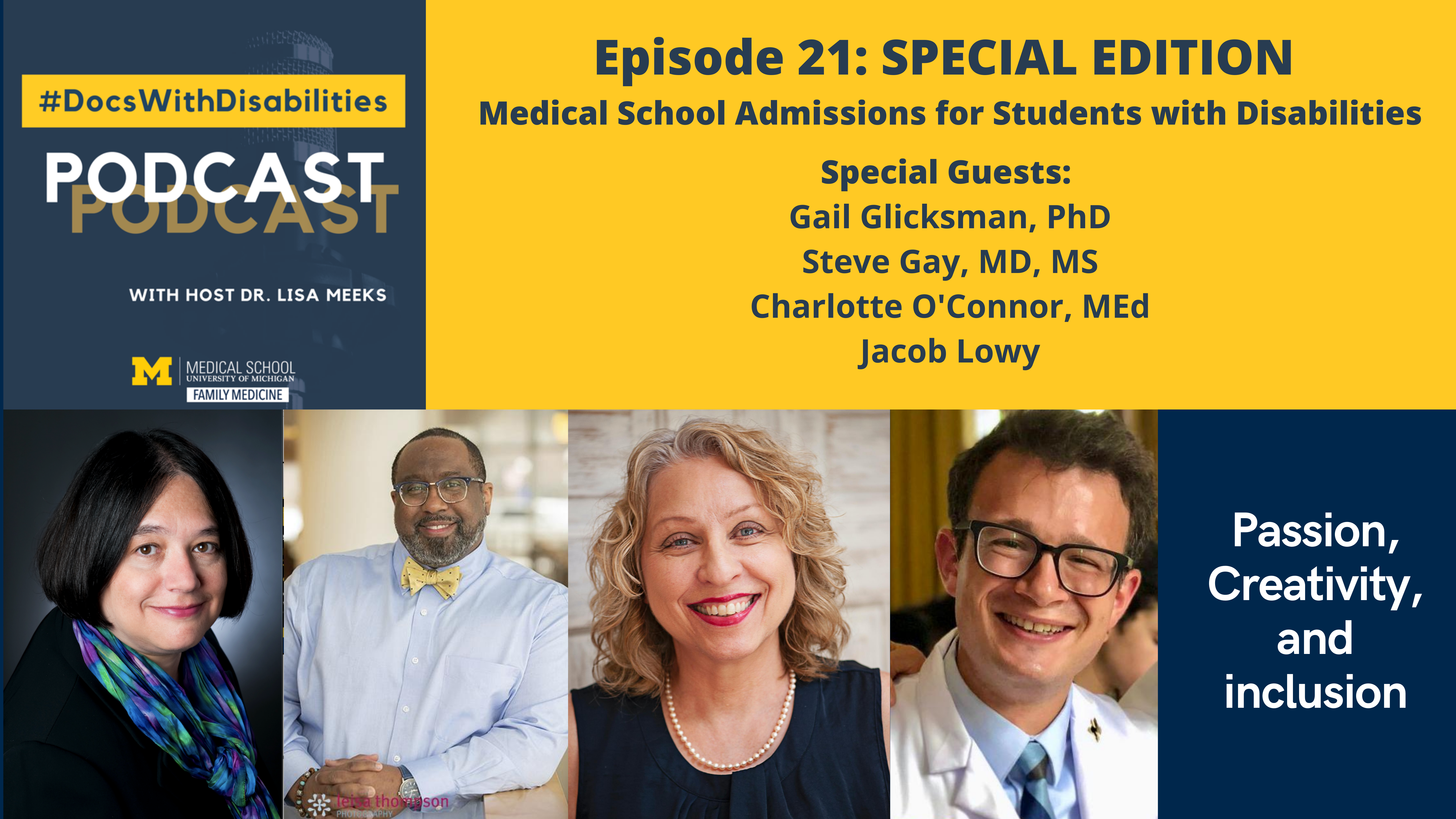

It's always a delight to speak with an audience of health-professions advisors, because you are uniquely situated to remove barriers for learners with disabilities, through your support, your advisement, and the sharing of resources. Today, I am joined by an incredible dream team panel, including Gail Glicksman, the assistant Dean for health professions advising at Bryn Mawr college; Dr. Steven Gay, the associate professor of medicine and Dean for admissions at the University of Michigan Medical School; Charlotte O'Connor, the learning and disability specialist at the University of Michigan Medical School; and Jacob Lowy, a medical student at the University of Michigan Medical School.

So first I'd like to start with Dr. Glicksman, who developed our original submission for the conference in response to an increasing need for disability related information from her colleagues. So Gail, what do we know about the premed landscape? What beliefs do people have about the ability of individuals with disabilities to enter medicine or other health professions?

Gail Glicksman:

Of course. Dr. Meeks, as you've already pointed out, competition for admission to med school is very intense. Students worry that they must be perfect to gain an interview, let alone to be admitted. Culturally, there's a powerful perception that physicians as healers must be perfect, omnipotent, omniscient and you name all of the other ways that they must be perfect. Medical schools today require competencies that are broad, interpersonal, intrapersonal, academic, in many other ways that are higher expectations than I've seen in my experience advising over some decades.

So this perception, this cultural perception, I believe might even be reinforced by the observations now of the physicians and other health providers and how they're responding with such dedication and some are describing it as super human, heroic commitment to their patients. It is very impressive, but it’s also impressive to realize that individuals can contribute a tremendous amount to their patients and to the field of medicine without being "perfect" in any ways in, in all ways. And indeed those who are aware of challenges of some sort are in better positions to use strategies, to be able to meet the challenges that they face.

So students are concerned about whether they can meet the standards, even if they’ve begun to show talent in academic and other ways. And those fears are often magnified and fueled by well intentioned, but respected figures, whether in their own family, whether faculty members or advisors, of general academic advisors. And those individuals might be very well intentioned, but might be ill informed and not aware of recent developments and changes in the landscape of medical training and practice.

Some respected advisors, not necessarily premed advisors, have told them that medical schools will realize they've used accommodations, especially if they need anything in their interviews and that they would be disqualified given the competition.

Some have even said in very hurtful ways, “Well, if you need extra time on exams in my class, what will you do in the medical environment if I were to need emergency care? Would I want a physician who needed a little extra time to process the information about my case?” And that's very hurtful. And it discourages some premeds who don't even go further.

I think the next challenges involve disclosure. As you mentioned that these narratives of ignition are cultivated, highly prepared over a long period of time. And frequently an individual who's experienced health issues of any kind might trace their interest in medicine to their experiences with the situation. And that makes them especially concerned because they want to be genuine, but they worry that in a one page statement that they want to make sure that admissions officers don't dismiss them just because of that.

And the next concern that students typically express is, well, I think I can handle this. I can move forward and I can figure out how to craft a personal statement that expresses what I want to say, and that might or might not disclose. But how do I find an environment that would be a good fit for me, that would be welcoming and inclusive?

Lisa Meeks:

Thanks so much Dr. Glicksman. Thank you for setting up the landscape. This is a perfect transition into talking about the admissions process. And so we are so blessed today to have Dr. Steve Gay, the Dean of admissions here to talk to us about some of the process at Michigan and some of the work that he's doing on a national scale to increase the number of students with disabilities in medical education specifically. So Dr. Gay, we now turn to you as this leader for admissions. We know that all premed students carefully construct their narratives when writing application essays and preparing for interviews. As Dr. Glicksman pointed out, many of them are coming to medicine because they've had a personal experience with their health or mental health. And they're trying to consider the aspects of their experiences to discuss, how to respond to sensitive questions that they may face. They also may face additional questions about disclosing information in their essays or during their interviews. So my question for you is:

What factors should admissions advisors consider when helping students evaluate whether to disclose their disability during that admissions process? And if so, what stage of the process is the best stage to do this disclosure?

Steve Gay:

Thank you very much Dr. Meeks. To start with when to disclose, let's start a little bit about what we actually are trying to glean from the admissions process. It isn't just about knowing whether or not you have great grades or scores. It is very much about understanding the context of your journey and how you have succeeded in the context of that journey. If what you have gone through is an important part of your narrative, that shows a great deal of resilience, that shows a great deal of strength. It shows so many of the attributes that are core competencies for what we hope to see out of our physicians.

So when to disclose. If it is an important part of the context of your journey and your success, please disclose it. If you feel that you may require accommodations during the interview day, please disclose it. We as medical schools want you to perform at your best level. We don't want to try to figure out if your performance wasn't what you would have liked it to be because we didn't know something about you. We have to judge you on the performance you've presented with. And so if you need accommodations to perform at your highest level during your interview day, please let us know.

Please let us know after you've been admitted. We want you to succeed as a medical student. Your medical career, we'll start with the most difficult year or two academically that you have ever encountered. We want you to have every ability to work at your highest level and want to be able to supply to you any accommodations that you may require to do so. Now I understand that many are concerned, will they not choose me? Will they not select me? Will they not consider me in light of my disability or the potential need for accommodations? I actually look at that in a very different way. If you have someone that does not understand the context of your journey, if they are not willing to aggressively participate in your potential success by supplying appropriate accommodations, then that is not an institution you wish to attend. You have to be, as a selective consumer, aware of places that will work as hard as they can with you to ensure your success in medical school.

A place that doesn't want to know about potential accommodations, does not want to understand the context of your struggles in your journey, that is not enlightened to understand that achieving in light of those things is an exceptional achievement, probably isn't a place that we'll be looking to assist you to thrive and do your very best to achieve your dream of becoming a physician. And so I think it takes an appropriate evaluation by each student of institutions that will look to do everything they can to assist you to become what you've dreamed of.

Lisa Meeks:

Thank you so much. That's pretty powerful Dr. Gay. I’m wondering, just a follow-up question on that.

Does your advice hold constant for students that have both apparent and non apparent disabilities?

Steve Gay:

Yes, it does. Once again, it is about the context of your journey. If you have achieved in light of challenges, that is both a very compelling narrative, but also a very strong indicator that during your medical and professional career, when confronted with challenges, whether or not it's a patient that's undergoing an arrest, whether or not it's a complicated administrative role that you've taken on, when you have shown the ability to overcome in light of difficulty, we have faith that you will be able to do so again. My committee has great concerns about a student who presents themselves with doing everything perfectly and never having an issue, problem, or concern. We worry that that student didn't push themselves to the limits and challenge themselves. We know in medical school that will occur, that you will be put under significant challenges, significant stress.

And we are going to want to know that it isn't the first time that this has occurred. We are going to want to know that you have shown the ability to take on a challenge and overcome it. So in terms of becoming the medical student you wish to be, I think it is very important to disclose things that you have achieved in light of. I think it is an incredibly important portion of your journey, a very important portion of your story. And I think it does help us to know and understand in those competencies, such as adaptability, resilience, desire, strength, that you possess them. And so I think that's the way I put it to applicants that ask me what they think they should do.

Lisa Meeks:

Thank you so much. And I'm going to take a second. I'm sorry if this is embarrassing, but I'm going to brag about you for just a second, because I get the absolute honor and pleasure of sitting on your committee. And I have watched you through your leadership really live the words that you are saying. You truly embrace the idea that there are benefits to being a person with a disability and having experienced things. And I think that students with disabilities genuinely get a review that is balanced and favorable in that Michigan understands that value. Because I imagine there are admissions offices listening to this podcast as well, I wonder what advice you would offer to other schools about making their admissions processes more accessible to individuals with disabilities?

Steve Gay:

Thank you very much for your kind words, Dr. Meeks, I deeply appreciate it. I think the first aspect to do this is to know and understand what your goals, aims, vision and mission is not only as an office of admissions, but as a steward of your medical school and for your medical school. Knowing and understanding this, knowing and understanding the qualities that are important to succeed at your school, knowing and understanding the capabilities of what your school can do and can supply to your students for their success. And this is for every single student with or without a disability from various backgrounds, from various socioeconomic issues and concerns, on and on. You have to know and understand and be a part of the decision making process for your institution to know what will be required and what will be supplied and what your institution is willing to do.

And if your institution looks like it may be falling short on that, it's to point out to your institution the benefits of putting in processes that will assure the success of your students from any background and at any level. The most difficult thing we can do as an office of admissions is bring in a student and have them not succeed. It isn't simply on the student for their success. We have to create an environment, a culture, a community that is willing to support them and give them the opportunities to perform at their highest level, the opportunities to explore everything to be the type of physician that they have dreamed of.

If we do this as an office of admissions, if we work with our offices of student services, if we work with our senior leadership to develop a vision of who we aspire to be and what we aspire our students to achieve and attain, we do better as an institution because we have a focus and we have a way to work through it that will work to ensure their success.

Lisa Meeks:

I'm getting a lot of inquiries about technical standards for those schools that are struggling with rewriting their technical standards, to make sure that they're accessible. You recently led a chapter on that topic so they can find that as a resource as well. So I just want to thank you. And I want to thank you for the work that you do and thank you so much for being part of this panel. We know that disclosure is such a personal decision and multiple factors go into deciding whether or not to disclose. And I think you gave a really balanced impression of how a student should go about that. I agree with everything that you said.

And of course, one factor that plays into this decision for the student is the culture of an institution. And while students may feel safe to do that at Michigan, they may not feel safe to do that more broadly. I think that there are resources for helping students make these decisions. And so that brings us certainly to our next panelist, Charlotte O'Connor.

And Charlotte, when students do successfully matriculate into health professions programs, they do need to make these difficult decisions about disclosure. And I know that your office receives a ton of requests. Some of the things that I know that, in my conversations with Dr. Glicksman, she had mentioned that her colleagues were concerned about finding the best sources of accurate information about medical schools and disabilities, how they can identify schools that have a commitment to inclusion? What are the most effective ways to identify a school's technical standards and access services? And what about policies for accommodation? I'm wondering Charlotte,

Can you speak to these questions about finding information and what resources do you think are the must haves if you will, for students and pre health advisors?

Charlotte O'Connor:

Thanks Dr. Meeks, I'd be happy to do that. I want to, just as a caveat, tell our listeners that there will be links to all of these resources, because there are quite a few that I'm going to go through right now. And I've broken them up by audience. And so I’ve started with, for the students, as you're investigating medical schools to apply to, look over your prospective school's website in its entirety. And if you're having difficulty finding information about disability, that perhaps could be a red flag. Look at the medical school's web page, look for the technical standards and read those. That's very, very important to do. Reach out to the disability services provider at your school. These people are really happy to talk to you, and I can speak from experience. I frequently get calls from students who are considering applying to Michigan, and I am more than happy to talk to them about how we will accommodate disability in our medical school.

Then after acceptance, sometimes students are still not sure if that's the school they want to matriculate to. So that's another time to reach out to your disability services provider at the school. I work very closely with the admissions office, and they'll refer students to me who call with questions as well. Look at the association of American Medical Colleges website. They actually offer guidance for pre-meds and medical students with disabilities. They have things ranging from making your application to interview tips, to surviving school with chronic illness or a disability. Read the AAMC's journal, academic medicine. If you do a search on the term disability, you'll find a multitude of articles about having a disability in med school. Also, see the Journal of American Medical Association, JAMA. It includes a column called A Piece of My Mind, which includes some first person accounts written by doctors with disabilities.

For advisors, I would say everything I've just recommended to students would be great resources to get a good broad view of what's out there and what's available. Join a professional organization. The Coalition For Disability Access and Health Science Education is an organization of disability service providers in the health sciences. Network at their conferences, read their listservs.

Another organization is the AAMC, which has a wealth of information. You can attend their archived webinars. There are 10 available from the website, and that will give you a sense of what reasonable accommodations look like in med school. Also, you can join the Medical Educator Learning Specialists, special interest group of the AAMC. As the work of medical school learning specialists in disability providers intersect, they have a robust listserv, you'll make contacts, you'll get to talk to people at other institutions, post questions, get answers. It's a wonderful resource. And read the American Association of Medical Colleges report, Accessibility Inclusion in Action and Medical Education, Lived Experiences of Learners and Physicians With Disabilities, which was published in 2018. And it discusses best practices and offers wonderful advice.

Identify the med schools your students attend most frequently if you are an advisor, and reach out to the disability resource providers at those schools. Find out what they do, what they don't do and then you can share that good info with your students. Students don't know what they don't know. So they don't have answers, they sometimes don't even have questions. And applying to medical school for a student with a disability requires so much work. So this is really a step that you could do to make those students' lives so much easier.

Read the newly published book, Disability is Diversity, which I had the honor of contributing to, a shameless plug here. But especially chapters four and seven, they discuss creating a culture of inclusion and accessibility. And for everyone, listen to the Docs With Disabilities Podcast. You'll learn about what current physicians with disabilities are doing, where they trained, where they're working, and you can keep abreast of what's happening in the field of medicine.

Also, Twitter has a very active following. If you look for #DocsWithDisabilities, for their stories. There are also student led networks for disabilities as well. @DisabledDocs, you'll find Future Docs With Disabilities, which is a grassroots mentorship network. That was a lot of resources to throw at you, but there's a lot out there. So avail yourself of them and you'll have great resources to help your students.

Lisa Meeks:

Thank you so much Charlotte. I think that's one of the biggest things that you can do for someone, is to give them resources, give them a toolbox to go to when they have questions. And so I think that was so valuable. I also want to add that of all of the resources you've mentioned, even though several of them are med centric, that they really do apply across all health science professions. I know personally all of the webinars have information that is really rich, and although developed for a medical school environment, the same principles can be applied broadly. And so I don't want to miss out on the advisors that are advising students about nursing school and physician's assistant school, occupational and physical therapy, speech language pathology, all of those programs. A lot of the same principles apply.

Charlotte, I have a follow up question for you because so many of our students have to go through not only an interview as part of their admissions process, but there are evaluations that are associated with the admissions review like the Casper or the MMI. Even physical logistics of interview day can seem overwhelming potentially to a student with a disability. What should students do if they feel they need accommodations on these assessments or in the physical space?

Charlotte O'Connor:

I work closely with admissions. And so if they tell admissions that they'll need accommodations, I will definitely arrange combinations for that day. Michigan's website actually has a link that will take you directly to the page on which you apply for accommodations for Casper. But that is not a problem, that is what I'm here to do or if students would want to reach out directly to me, I could initiate that process as well.

Lisa Meeks:

That's awesome. I do want to highlight that you are actually situated in the school of medicine. So you are the learning specialist in disability service providers specifically for medicine. That was one of the recommendations I know in the book you discussed and it's a recommendation that's coming out very frequently, whether it's health science specific or medicine specific, that there's just such a nuance in these clinical accommodations and the needs for students with disabilities entering health science professions. So having that expertise is really helpful. And I'm so grateful that we have you at Michigan and thank you so much for sharing those resources.

This translates really nicely into our fourth panelist Jacob Lowy. And Jacob, you're a student with a disability at the University of Michigan Medical School who is using accommodations. And I'm going to give you a lot of free reign here Jacob. You know your peers, you know what you experienced going into medical school. Can you tell us about your experiences and why you chose to disclose?

Jacob Lowy:

Absolutely. So I am going to upfront just say, I did not disclose during my application process and I waited until after I was accepted to medical school. And in retrospect I would have disclosed much earlier, but I was to be quite honest, afraid of looking weaker as if I had an issue that might count me out in the admissions process. Knowing what I know now as a medical student, I don't think that would have been the case. And I actually think it would have made for a more compelling application to medical school. So in hindsight 2020, but I would have disclosed much earlier if I could have. And part of the reason why I didn't disclose as well as because for much of my life, I was discouraged from utilizing accommodations or reaching out for support.

I have unilateral hearing loss in my right ear, and I was born with that. And from a young age, when I had a hearing aid, I felt very insecure about it. I didn't receive a lot of support in elementary school for that, and my elementary school and the school district I was in actually discouraged my family from seeking accommodations during my childhood. So I grew up with much of my life learning to just sit in the perfect place so that I could hear out of my left ear, making sure that I was always thinking about where I was listening to people in the classroom, in social situations, at restaurants. Everyone always thinks that I'm really, really engaged in conversations because I have my head turned directly to them. But it's mostly because I'm lip reading or paying very close attention to them.

So I guess that actually plays in my favor sometimes. But just the fact of the matter is much of my life learned how to adjust. And I went to a small liberal arts college for undergrad and did not utilize any accommodations there because classroom sizes were 10 to 15 students. And I would just continue to do my usual routine of positioning myself. I worked for a few years after college and did not use accommodations there because I had a lot of one-on-one interactions with my boss. And then I went to a post baccalaureate program and also did not use accommodations there because it was a small program. And approaching my application process, like I said earlier, I did not want to show any type of weakness and in retrospect, I do not believe my hearing loss is a weakness of any kind. In fact, I feel like it gives me a lot of insight into what it's like to live with some type of a disability. And it gives me a good perspective on how patients are experiencing different issues that they have.

But at the time, medical school on its own, the application process seems daunting from the get-go. You want to make sure all your MCAT scores and your grades are all as high as they can be. You want to make sure that you've got great recommendations. You want all your extracurriculars. I would worry that my application could get thrown out if I had a couple of typos. So I didn't want to leave myself open to any issue as I applied. And I also knew that I could get through one-on-one interviews relatively well and I felt like the benefits of just not disclosing at the time seemed worth it to me and I would take the risk of just not telling anyone about it and maneuver my way through interviews like I had maneuvered my way through much of my life.

The decision that I made to disclose came a few months before I matriculated to the University of Michigan. I was volunteering in an operating room in Baltimore at the shock trauma center at the University of Maryland. And I realized that I couldn't hear or understand what the surgeons were saying. It's because they were wearing masks and I couldn't lip read. And I had stopped using a hearing aid when I was six or seven, because I felt very insecure about that. And I realized that going into medical school, if I ever wanted to do anything in an operating room at a minimum, I would need to have a hearing aid.

So I went and for the first time in maybe 20 years, I got evaluated for my hearing loss and I got a great hearing aid that has made a tremendous difference in my ability to interact in ORs, in clinical settings, in classrooms. And then we got an email from the University of Michigan and this was right as I was deciding to go here asking us to sign the technical standards, and I had not at that time yet disclosed my hearing loss. And I kind of freaked out because the technical standards at the time said that I needed to be able to demonstrate that I have visual, auditory and somatic sensation and that I would not have compromised communication skills. And I obviously, with my particular disability, felt that I could manage all those things even without a hearing aid. And I knew that I could demonstrate it with a hearing aid too that I would be able to hit all the technical standards.

But at the time I was actually worried that I was going to get penalized for having not disclosed in the application process and waiting until after I was accepted to disclose. And of course, whenever you need to come forward and say that you have a disability, there's no wrong time to do that. And I obviously was not penalized and I was embraced for bringing my disability forward and getting additional support from Michigan. But at the time as an applicant, I was worried that the admissions office would think that I had somehow by not disclosing had deceived them or hidden something. And obviously that's not the case.

So coming forward, it was a very stressful process for me. I had never learned to advocate for myself in a significant way with my hearing loss prior to medical school. I think that one of the challenges of having some type of a disability or any type of disability is that you have to be your own best advocate as a student. And I think that advisors can really help with this too, but students, especially in higher education, the mandate is on students to come forward and disclose their disability. No one is really seeking out and trying to figure out whether or not every single student has some type of an accommodation they need. The onus is on the student to come forward. And that's a really daunting task sometimes because you have to be able to document everything and show that you have a disability and then you have to be able to describe the type of accommodations that you need.

And quite frankly, walking into medical school, I was not sure of what accommodations I should be using, what I should request, what I needed. And I was fortunate that the office for the students with disabilities at the University of Michigan was very helpful in going through my options. I ended up using a real time translator during my first year of lectures, and I actually had someone translate and type every single lecture down as they were going on. And I could read it on my screen. I also got access to augmented stethoscopes and was given advisers who have hearing loss at the University of Michigan who have been particularly helpful in guiding me through thinking what type of support I need. So in retrospect, the earlier that I'd come forward I think, the better, and I'm glad that I did when I did.

Lisa Meeks:

Thank you so much Jacob. That is going to be so helpful to both the students listening to this podcast and the advisors. I want to follow up on a couple of things that you said. You mentioned the technical standards, and I want to give Dean Gay an opportunity to respond, because I know that we've changed our tech standards. And Dr. Gay, can you maybe talk for a second about why we changed our technical standards. What was the impetus to addressing the changes?

Steve Gay:

Thank you Dr. Meeks. I think there are a number of significant reasons. One, I am grateful that we have become more conscious and enlightened as an institution to be blunt. We have had some transformational students with disabilities who achieved at the highest levels at our medical school, and they have been advocates. They have educated us. They've made it very clear that we can do things better than we do. It is also, however, a philosophical belief of our medical school, that what we are here to do more than anything else is to teach you to think to be a physician, how physicians think and decision-make. And if we teach you that, then the opportunities are endless. No, graduating from our medical school is not tested approval that you can do any residency that you wish, that's true for every single student. Students find their areas of excellence and they pursue them.

The combination of those factors has been very important in how we have designed our technical standards. Simply put, we want you to be able to learn, interact, disseminate information, assimilate information with or without accommodations, to the extent that you will get through our curriculum and be successful in our curriculum. It is about graduating from the University of Michigan Medical School, with the skills to think like a physician. When you approach your technical standards in that way, it becomes very clear the things you can offer, the things you can do, the things that you should be able to do as an institution to support your students.

It fits in very closely with our goals of medical education, to create leaders and change agents in healthcare. It is not for us to tell you what you will lead or what you will change. That is part of the journey of each and every single one of our students in their own unique way. But it is crucial that we teach them to think and problem solve like physicians to achieve that goal. And that is the goal of our technical standards, to work, to assure that our students can and will thrive in our curriculum.

Dr. Meeks:

Thank you so much. And the chapter that was Michigan led by you and Dr. Mckee, it actually has a self evaluation portion where schools that are looking to renew or revise their technical standards can walk through that process. And I think a lot of the philosophical approach was captured in that writing so beautifully. So thank you again.

Jacob, you mentioned the law and how you felt like you might be punished. I do want to give Charlotte an opportunity to talk about what the law says about disclosure and how students can disclose at any point.

Charlotte O'Connor:

Sure. The students can disclose at any point in time and the law supports the fact that we are obligated to make the curriculum accessible. And so you will never be penalized for having a disability.

I always encourage students to disclose early because if you do hit barriers, they can be perceived as perhaps that you're not trying, or that you're unprofessional. And so it's really important to disclose early. And it also sometimes takes time to get through that interactive process and to determine exactly the appropriate accommodations that you're going to need in medical school, because medical education is unlike any other higher education that I've ever experienced in my close to 20 year career working with students in higher ed.

And so if you've never been in that setting, you may not know what you need. So it's almost, I refer to it as a, it's a process. Sometimes it's guess and check. We do our best and then we have to tailor it to every individual as we go along. So the sooner we know, the greater the opportunity we'll have to reduce those barriers.

Lisa Meeks:

Thank you so much, Charlotte. I do want to recognize that while this is a Michigan panel, there are multiple schools across the nation doing really good work for inclusion. And so while we would like to believe Michigan is the best school for everyone, there are individuals who are looking at other institutions, and I want to assure you that Michigan isn't the only one, that several institutions are doing this good work, are truly accessible and there are people like Charlotte across the country situated in these medical schools or on these health science campuses that are highly qualified, extraordinarily friendly, and would welcome your questions as a premed advisor.

So I really liked Charlotte's idea about reaching out to the top four or five schools and having those people all meet not only one another, but to inform your practice. So I think that's a fabulous idea. And Charlotte and Jacob, you both touched on this idea of, you don't know what you don't know. And so we truly need individuals to reach out to students proactively. And I know Steve, this is part of what you changed in the technical standards and in some of the work was to have language that really encourages students to come forward and to request accommodations or to inquire about the process. And just to let them know that it's there, I think that transparency is so critical.

I do want to go back to Dr. Glicksman who... First of all, I just want to thank you so much for putting this panel together and for coming up with the creative idea of a substitution for the actual presentation down in New Orleans. And so we're so grateful to you. I want to end the podcast with advice going down the list of our panelists. And I would ask if you had one piece of advice you could share with a premed advisor or with a student, take your choice. What would it be and why? Why is this a critical piece of advice? And so we'll start with you Dr. Glicksman.

Gail Glicksman:

Thank you. My advice to both a premed student and to an advisor would be to reach out, explore and connect with individuals. So all of the resources that Dr. Gay, Dr. Meeks and Dr. O'Connor have mentioned, and that you'll find in the transcript for this podcast would be wonderful places to start. Explore, connect, find out what's going on.

Lisa Meeks:

Thank you. Dr. Gay?

Dr. Steve Gay:

I think if I were to give any advice to the students, embrace the context of your journey, be proud of it, allow it to reflect your success. And while you were doing so, search for institutions that not only will help you to achieve the goal of exactly who the type of physician you will be, but will be supportive of you during that journey, that will work to protect you during that journey.

Lisa Meeks:

Thank you so much. Charlotte?

Charlotte O'Connor:

I would say, do your homework, do some research, make sure that the fit is mutual. I think often students are so worried about impressing and wanting to be accepted. I advise that it goes both ways. It has to be a good fit for you as well. And so reach out, ask questions and make sure you're finding a good fit.

Lisa Meeks:

Thank you Charlotte. Jacob?

Jacob Lowy:

I have to say I was going to say something very similar to Dr. Gay. I think that embracing your disability and your journey and your experience is probably the best thing to do as you move into your medical school application process. Of course, I'm speaking on this from the other side now as a medical student, but being able to bring out who you are in an application really matters. And my hearing loss has been a very integral part of who I am as a person. And I did my best not to present that in my application process because I didn't want to look weak, but I think that bringing that forward for each and every person and speaking about it in a way that feels good and true to you is important. So being true to yourself as you apply to medical school is probably my best advice.

Lisa Meeks:

Jacob, that's really good advice. And I think Dr. Gay and Dr. Glicksman and Charlotte would agree that when you bring forward your authentic self, you are presenting your best self and that authenticity and that genuineness goes a long way. So I think that's really, really good advice.

I also want to add Jacob, I know you and I had a conversation a few weeks ago about the unique situation with you having had that experience in the surgery center. And now as we go through this pandemic, we talked about how uniquely qualified you are in this situation to understand what patients are going through and what they're feeling when they encounter a person whose face is covered up, the mask is on, and they can't quite understand what's happening and communication is at a premium essential. And we're in quick communication, quick response and how disorienting that may feel for the patients.

So I just want to point that out, is just one situation where somebody coming to the table with a disability is able to inform how we interact with patients in the midst of this pandemic, in the midst of this crisis, and may alert providers to a situation that they're not thinking about right now. They're thinking about how do I save this person? And they may not be thinking about how scared this person may be as a function of not being able to communicate.

I want to thank all of you. I know, especially in my work I'm with you Dr. Gay and you Dr. Glicksman, you've become such a great advocate for disability inclusion in the premed front. And Charlotte, I truly appreciate the opportunity to highlight the work you've been doing and to bring this information to the public. And we'll just end by me saying, I am full of gratitude for your work and for your partnerships. And I thank you. I think that the listener now has a list of resources that are too big to list, but we will have those in the transcript. So please do check out the transcript and keep following us. There's more to come. Thank you all so much.

Kate Panzer:

Thank you to our wonderful panelists for sharing your insight and perspective on the admissions process and accessing accommodations. And thank you, our audience, for joining us. In our next episode, we will chat with Dr. Walker Keenan, a psychiatry resident at Yale School of Medicine. Until then, we hope you stay safe, stay well, and stay connected with one another.

This podcast is a production of the University of Michigan Medical School, Department of Family Medicine, MDisability initiative. The opinions expressed in this podcast do not necessarily reflect those of the University of Michigan Medical School. It is released under a creative commons, attribution noncommercial, nonderivative license. This podcast was produced by Lisa Meeks and Kate Panzer.

*This podcast was created using excerpts from the actual interview and is representative of the entire conversation. Interviewees are given the transcript prior to airing. Some edits may reflect grammatical and syntax adjustments for transcription purposes only.

Resources mentioned during the podcast.

Dr. Gay’s chapter on technical standards in Disability As Diversity

https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783030461867

AAMC.org

-Medical Education Learning Specialist Special Interest Group (MELS)

https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/affinity-groups/gea/negea/special-interest-groups

To join MELS, contact: Hanin Rashid - [email protected]

-Accessibility, Inclusion, and Action in Medical Education: Lived Experiences of Learners and Physicians with Disabilities (2018)

https://store.aamc.org/accessibility-inclusion-and-action-in-medical-education-lived-experiences-of-learners-and-physicians-with-disabilities.html

-Disability in Medical School

https://students-residents.aamc.org/search/?q=disability

Books

Disability as Diversity: A Guidebook for Inclusion in Medicine, Nursing, and the Health Professions 1st ed. 2020 Edition, by Lisa Meeks (Editor), Leslie Neal-Boylan (Editor)

The Guide to Assisting Students With Disabilities: Equal Access in Health Science and Professional Education, by Lisa Meeks and Neera R. Jain, 2015

Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA)

- A Piece of My Mind (Opinion Column)

https://jamanetwork.com/collections/44046/a-piece-of-my-mind

The Coalition for Disability Access in Health Sciences Education

https://www.hsmcoalition.org/

https://www.hsmcoalition.org/listserv

https://www.hsmcoalition.org/webinars

Twitter

#docs with disabilities

@disabled_docs